Do you not marvel at the latest scientific discoveries when you hear about them? Undoubtedly, there are one of two responses that grace your mind:

"Those crazy scientists, there they go again! They keep changing their story."

or...

"Really, how interesting! So, how does this then affect [You provide the list here...].

The other day I ran across an article about a topic with which I am only nominally familiar, string theory. I teach this in my astronomy classes, but I cannot fathom the math involved. Specifically, this article talks about the possibility that, within the greater universe there are "pockets" where other universes with different laws of physics might exist. Inflation theory and string theory together predict that our universe is just one of a nearly infinite number of possible arrangements for any given universe. In essence, when speaking of "the universe", we ought to instead refer to "the multiverse".

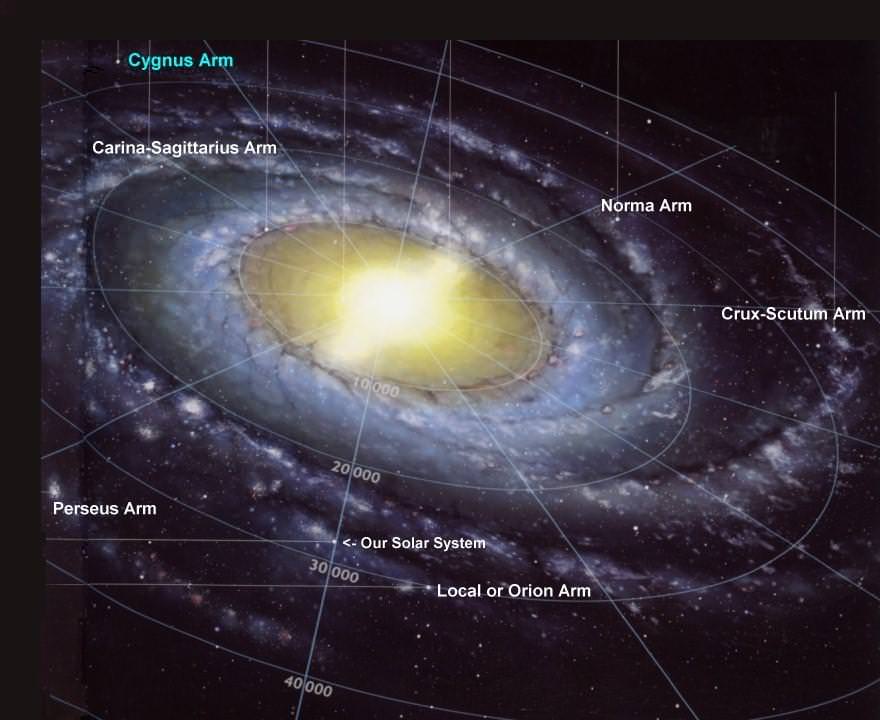

To be sure, these ideas dwell on the border between science and philosophy, in large part because physicists just are not able to easily test these ideas at the moment, though they are certainly trying. They are looking for evidence, but they are limited by their environment. We can not see past the Big Bang or the speed of light. This is not at all an unusual position for scientists to find themselves in, albeit it can be a frustrating one. For most of human history, the band of billions of stars in our night sky that we now know as the Milky Way galaxy was just thought of as a "Milky Road" or "Milky Circle" -- a path followed by the anthropomorphized constellations, deities and heroes, through the heavens. Of course, we now know that it is something we call a galaxy, which is a huge collection of stars located within a larger group of galaxies, etc. For centuries, western philosophers and scientists had suspected that the Milky Way was a group of faint stars, but Edwin Hubble was the first to provide proof of that, in the 1920's! It took 2000 years to go from the first recorded ideas by ancient Greek philosophers to the current scientific view. In all that time, we were want of any evidence to support the idea...only scant observations by Galileo and gravitational calculations by Kant.

Today, these new discoveries seem to occur at breakneck speed. We now know that our galaxy, once a typical spiral galaxy, is now thought of as a barred spiral (Sbc) galaxy. Who knew! String theory and this idea of multiverses will be no different. It will be difficult to keep up!

We truly see very little -- "through a glass darkly" (I Corinthians 13:12) -- and not just in areas of faith. We see what is immediately around us and assume that is all there is to know. We are myopic, stuck in a box. Our faith can certainly be this way. This passage of Corinthians is one Biblical passage that has much to say about how science works: "As for knowledge, it will pass away" (verse 8); "When the perfect comes, the imperfect shall pass away" (verse 9). These words are so true. We tend to put God in a box and fail to see what He wants to show us about His creation. Ironically, it is scientists who, though they do not aim to find God, perhaps come closest to understanding the true magnificence of His creation when they push the limits of our knowledge of it. Old knowledge passes away and makes way for new knowledge. Imperfect ideas give way to something closer to a perfect understanding of creation.

When I contemplate the idea of a multiverse universe, I can not help but be floored by all of its glory and variety, and reveling in God's majesty and creative fervor, I am once again reminded of humanity's perennial myopia. We put limits on God based upon what we read in His word -- perhaps, when it comes to the natural world at least, we should allow Him some greater latitude?

Monday, June 4, 2012

Thursday, January 19, 2012

What is a Scientific Theory Anyway???

"A theory is a good theory if it satisfies two requirements: It must accurately describe a large class of observations on the basis of a model that contains only a few arbitrary elements, and it must make definite predictions about the results of future observations."

"A theory is a good theory if it satisfies two requirements: It must accurately describe a large class of observations on the basis of a model that contains only a few arbitrary elements, and it must make definite predictions about the results of future observations."

-- Steven Hawking (A Brief History of Time)

What are some theories in science? Evolution, plate tectonics, germ theory, relativity, etc.

My students struggle with the concept of a scientific theory. Franky, I don't blame them. It took me years before I finally had that epiphany moment where I finally saw through the muck of culture and understood what scientists were trying to say by calling something a "theory". I can relate to their confusion, in particular because of the frequency with which the term "theory" is bantered about in casual conversation or even in our minds as we reason through a problem...

"I have a theory that if I add some cheese to this meal, then my toddlers will eat it!"

Who wouldn't want to eat this??

A theory...really? At home, this is a phrase that unconsciously floats through my mind on those days when I am watching my picky toddlers and need to make them something for lunch. What else is going through my mind in such a moment? Well, Ezra will eat, or at least try, almost anything. But, he loves cheese in nearly any form. Joey, well, will eat hot dogs, fries, mac and cheese, and ocassionally chicken nuggets. Not much else passes his discerning gaze, let alone his lips. But, he at least also loves cheese. So, I reason that if I add cheese, perhaps I can make it look good enough to eat or perhaps cover up that little pea so he does not see it as he tries the food.

What do I know for sure though? They both like cheese. They are both more or less picky. But, is my mental statement above really a theory based upon the evidence that I have? Absolutely not. It is closer to a hypothesis, if anything. Really though, it is not even that. But, let us assume that it is at least a hypothesis. Why is it not a theory? Well, according to Steven Hawking (who just might know something about this), it does not satisfy either of the conditions laid out above. First, I am only applying cheese to this unique meal, one meal in the span of time. While I have applied cheese to other meals in the past hoping for a similar result, there were definitely other variables that were not adequately controlled for me to isolate cheese as the reason that the food was or was not eaten. So, even if my toddlers eat this meal, I cannot add this to my other positive cheese supplementing experiences in order to form a model for toddler meal cheese application. After all, I can only make a deductive argument about this one particular meal. My goal in producing a theory would be to attempt to satisfy an inductive argument that cheese application to a particular meal or possibly any meal at any time or place, would make it possible for my toddler to consider savoring their parent's culinary delights.

The fact is, not only can I not produce a model for cheese application based upon my limited observations, I certainly do not have enough basis to be able to predict that, in perpetuity, should I apply cheese to my toddler's meals, they will always joyously consume them in blissful indifference to any other ingredients, no matter how putrid those ingredients have seemed to my toddlers in the past (Joey's list is long here -- starting with anything containing chlorophyll).

To summarize my mental prognostications:

1) I can only make a single deductive argument in terms of this one meal as I did not adequately control other variables in previous meals where cheese application was used;

Therefore, I cannot produce a model that predicts an answer to an inductive argument for cheese application in all cases.

2) Since I cannot produce an adequate model for cheese application, I cannot therefore use this meal or any other experience to make an adequate prediction of what they will eat, should I apply cheese.

Therefore, I cannot call this a theory.

So, perhaps if all of us attempted to use the word "theory" correctly, there would be less confusion amongst the American populace when it comes to what scientists mean when they use the word.

Here is a suggestion. In my classroom used to hang a poster that outlined alternative words to use instead of insulting someone or complaining about something using expletives commonly used by teenagers (who tend to be much less picky with their food, by the way). Let's consider some substitutions for our situation:

Words to use to clear up confusion over the word "theory"

hypothesis (use this one sparingly though...we don't need MORE confusion :))

I would speculate that...

I assume that...

I suppose that...

My guess would be...

I have a premise that...

I would postulate that...(use this one sparingly also, lest my math teacher friends become angered)

I have an idea, ...

I propose that...

A quick look in that oh so forgotten reference book, the thesaurus, provides a plethora of preferable meritorious substitutions for "theory". Let's explore using them :)! Perhaps once we solve this dilemma, some of the conflict between religion and science will cease also.

My wife tells me that she is making rice balls with some vegetable purees hidden within them, at this very moment, for our picky toddlers (peas are banned from our house now, Ezra has shoved too many up his nose). And, yes, they contain cheese! Yum! Best of luck to her!

Joey, when he sees the carrot through the cheese...

Wednesday, January 4, 2012

The Star of Bethlehem

The Star of Bethlehem has been an enigma for 2000 years. What was it exactly? As we near the end of Christmastide, it is worth an exploration. Is there a fascinating confluence of faith and good science here? Or, is it simply a mythological plot device meant to bolster a story that some felt needed a bit of divine gravitas?

Few people would argue the latter. Most take the star quite seriously. And why not? There is nothing in the Gospel accounts of Matthew and Luke to suggest that the story was embellished with any intent to mislead. It seems to be a genuine event which led three very learned men from somewhere in the east, perhaps modern Iraq or Iran to Bethlehem. Perhaps, given their knowledge of Jewish scripture and prophecy, they were a remnant of the Jews who were exiled to Persia or Babylon but never returned to Israel. It is difficult to say for sure. In the U.S., we like to celebrate the star, the arrival of these men, the shepherds, etc. all at once in our nativity scenes. In reality, it is certainly very likely that they did not arrive to celebrate Christ's birth until some time afterward. In the Orthodox traditions, they celebrate this event on the Epiphany, January 6th, rather than at Christmas. Whenever it really happened, it is a truly fascinating story with potentially awesome astronomical story behind it.

So, what was this star that heralded such a momentous event in human history? This has been the subject of a great deal of debate over the centuries. One great place to start our modern exploration is the website bethlehemstar.net. There, you can read the list of qualifications they have compiled that any candidate star must fulfill. It's long, based upon scripture, prophecy, and its purported behavior. Here is the list:

1) It signified birth

2) It signified kingship

3) It had a connection with the Jewish nation

4) It rose in the east, like other stars

5) Herod didn't know when it appeared

6) It endured over time

7) It was ahead of the Magi as they went south from Jerusalem to Bethlehem

8) It stopped over Bethlehem

What a tall order! Personally, I see nothing wrong with this list. In thinking about the last 5, however, it is easy to rule out some of the explanations that have been proposed over the years:

1) A meteor -- Dramatic, but is fails on #'s 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and possibly others as well.

2) A comet -- In those days, comets were regarded as bad things. A bigger problem, however, is that there do not appear to have been any comets to see in either 2 or 3 B.C., the likely candidates for Christ's birth year. Also, Herod would have likely seen it. So, they aren't good candidates.

3) A Nova or Supernova -- Here is a neat professional article arguing for just that! They argue that it either occurred in a globular cluster in our galactic halo or in the nearby Andromeda galaxy. It is a great read...the author has really done a great job reasoning it out. So, this is actually a good candidate, even if this event was not necessarily recorded by ancient astronomers, as they often were.

4) A triple conjunction of Jupiter around the star Regulus in the constellation Leo. This is the Bethlehemstar.net argument, and it is also quite compelling. Check out the website for a more in-depth read.

I do not have a definitive answer on the question of the star. But, this seems to me to be an excellent example of a positive confluence of faith and science. The Bible, actually, is quite full of astronomical observations, so it is worth a read of some of those for anyone interested. One can spend a serious chunk of time marveling at how ancient people so deeply appreciated the heavens that most of us, with our GPS units and so forth, take for granted. So, I love these kinds of explorations! They lead me to wonder at the grandeur of the whole thing that we call the universe. This is a case where, as a scientist, I find my faith bolstered by a significant account of logical evidence -- a case where science and faith find some common ground.

Merry Christmas! Happy Epiphany!

Few people would argue the latter. Most take the star quite seriously. And why not? There is nothing in the Gospel accounts of Matthew and Luke to suggest that the story was embellished with any intent to mislead. It seems to be a genuine event which led three very learned men from somewhere in the east, perhaps modern Iraq or Iran to Bethlehem. Perhaps, given their knowledge of Jewish scripture and prophecy, they were a remnant of the Jews who were exiled to Persia or Babylon but never returned to Israel. It is difficult to say for sure. In the U.S., we like to celebrate the star, the arrival of these men, the shepherds, etc. all at once in our nativity scenes. In reality, it is certainly very likely that they did not arrive to celebrate Christ's birth until some time afterward. In the Orthodox traditions, they celebrate this event on the Epiphany, January 6th, rather than at Christmas. Whenever it really happened, it is a truly fascinating story with potentially awesome astronomical story behind it.

So, what was this star that heralded such a momentous event in human history? This has been the subject of a great deal of debate over the centuries. One great place to start our modern exploration is the website bethlehemstar.net. There, you can read the list of qualifications they have compiled that any candidate star must fulfill. It's long, based upon scripture, prophecy, and its purported behavior. Here is the list:

1) It signified birth

2) It signified kingship

3) It had a connection with the Jewish nation

4) It rose in the east, like other stars

5) Herod didn't know when it appeared

6) It endured over time

7) It was ahead of the Magi as they went south from Jerusalem to Bethlehem

8) It stopped over Bethlehem

What a tall order! Personally, I see nothing wrong with this list. In thinking about the last 5, however, it is easy to rule out some of the explanations that have been proposed over the years:

1) A meteor -- Dramatic, but is fails on #'s 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and possibly others as well.

2) A comet -- In those days, comets were regarded as bad things. A bigger problem, however, is that there do not appear to have been any comets to see in either 2 or 3 B.C., the likely candidates for Christ's birth year. Also, Herod would have likely seen it. So, they aren't good candidates.

3) A Nova or Supernova -- Here is a neat professional article arguing for just that! They argue that it either occurred in a globular cluster in our galactic halo or in the nearby Andromeda galaxy. It is a great read...the author has really done a great job reasoning it out. So, this is actually a good candidate, even if this event was not necessarily recorded by ancient astronomers, as they often were.

4) A triple conjunction of Jupiter around the star Regulus in the constellation Leo. This is the Bethlehemstar.net argument, and it is also quite compelling. Check out the website for a more in-depth read.

I do not have a definitive answer on the question of the star. But, this seems to me to be an excellent example of a positive confluence of faith and science. The Bible, actually, is quite full of astronomical observations, so it is worth a read of some of those for anyone interested. One can spend a serious chunk of time marveling at how ancient people so deeply appreciated the heavens that most of us, with our GPS units and so forth, take for granted. So, I love these kinds of explorations! They lead me to wonder at the grandeur of the whole thing that we call the universe. This is a case where, as a scientist, I find my faith bolstered by a significant account of logical evidence -- a case where science and faith find some common ground.

Merry Christmas! Happy Epiphany!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)