Do you not marvel at the latest scientific discoveries when you hear about them? Undoubtedly, there are one of two responses that grace your mind:

"Those crazy scientists, there they go again! They keep changing their story."

or...

"Really, how interesting! So, how does this then affect [You provide the list here...].

The other day I ran across an article about a topic with which I am only nominally familiar, string theory. I teach this in my astronomy classes, but I cannot fathom the math involved. Specifically, this article talks about the possibility that, within the greater universe there are "pockets" where other universes with different laws of physics might exist. Inflation theory and string theory together predict that our universe is just one of a nearly infinite number of possible arrangements for any given universe. In essence, when speaking of "the universe", we ought to instead refer to "the multiverse".

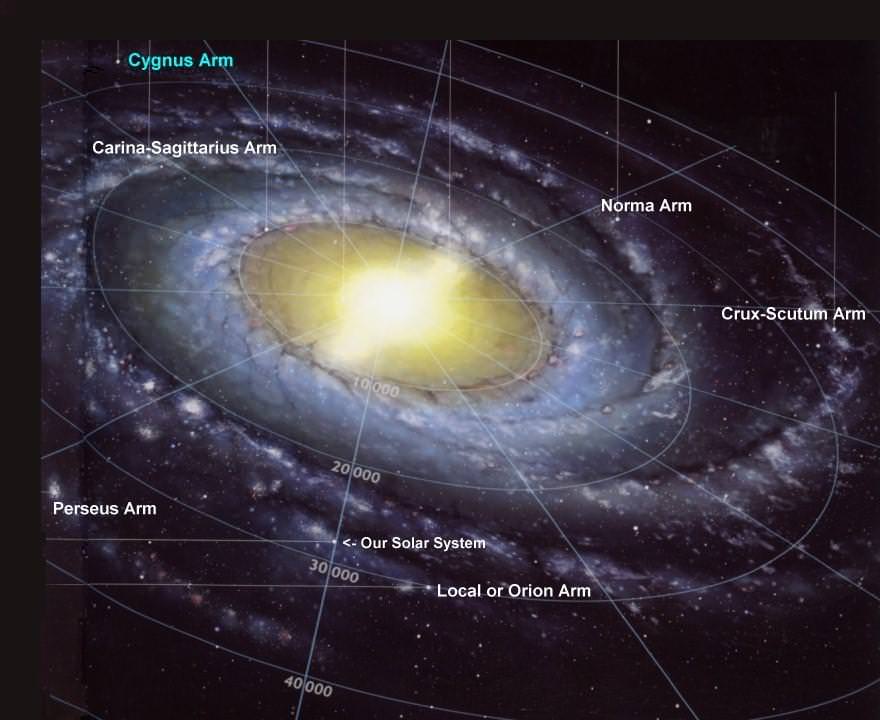

To be sure, these ideas dwell on the border between science and philosophy, in large part because physicists just are not able to easily test these ideas at the moment, though they are certainly trying. They are looking for evidence, but they are limited by their environment. We can not see past the Big Bang or the speed of light. This is not at all an unusual position for scientists to find themselves in, albeit it can be a frustrating one. For most of human history, the band of billions of stars in our night sky that we now know as the Milky Way galaxy was just thought of as a "Milky Road" or "Milky Circle" -- a path followed by the anthropomorphized constellations, deities and heroes, through the heavens. Of course, we now know that it is something we call a galaxy, which is a huge collection of stars located within a larger group of galaxies, etc. For centuries, western philosophers and scientists had suspected that the Milky Way was a group of faint stars, but Edwin Hubble was the first to provide proof of that, in the 1920's! It took 2000 years to go from the first recorded ideas by ancient Greek philosophers to the current scientific view. In all that time, we were want of any evidence to support the idea...only scant observations by Galileo and gravitational calculations by Kant.

Today, these new discoveries seem to occur at breakneck speed. We now know that our galaxy, once a typical spiral galaxy, is now thought of as a barred spiral (Sbc) galaxy. Who knew! String theory and this idea of multiverses will be no different. It will be difficult to keep up!

We truly see very little -- "through a glass darkly" (I Corinthians 13:12) -- and not just in areas of faith. We see what is immediately around us and assume that is all there is to know. We are myopic, stuck in a box. Our faith can certainly be this way. This passage of Corinthians is one Biblical passage that has much to say about how science works: "As for knowledge, it will pass away" (verse 8); "When the perfect comes, the imperfect shall pass away" (verse 9). These words are so true. We tend to put God in a box and fail to see what He wants to show us about His creation. Ironically, it is scientists who, though they do not aim to find God, perhaps come closest to understanding the true magnificence of His creation when they push the limits of our knowledge of it. Old knowledge passes away and makes way for new knowledge. Imperfect ideas give way to something closer to a perfect understanding of creation.

When I contemplate the idea of a multiverse universe, I can not help but be floored by all of its glory and variety, and reveling in God's majesty and creative fervor, I am once again reminded of humanity's perennial myopia. We put limits on God based upon what we read in His word -- perhaps, when it comes to the natural world at least, we should allow Him some greater latitude?

General Revelations

An Exploration of the Boundary Between Science and Faith

Monday, June 4, 2012

Thursday, January 19, 2012

What is a Scientific Theory Anyway???

"A theory is a good theory if it satisfies two requirements: It must accurately describe a large class of observations on the basis of a model that contains only a few arbitrary elements, and it must make definite predictions about the results of future observations."

"A theory is a good theory if it satisfies two requirements: It must accurately describe a large class of observations on the basis of a model that contains only a few arbitrary elements, and it must make definite predictions about the results of future observations."

-- Steven Hawking (A Brief History of Time)

What are some theories in science? Evolution, plate tectonics, germ theory, relativity, etc.

My students struggle with the concept of a scientific theory. Franky, I don't blame them. It took me years before I finally had that epiphany moment where I finally saw through the muck of culture and understood what scientists were trying to say by calling something a "theory". I can relate to their confusion, in particular because of the frequency with which the term "theory" is bantered about in casual conversation or even in our minds as we reason through a problem...

"I have a theory that if I add some cheese to this meal, then my toddlers will eat it!"

Who wouldn't want to eat this??

A theory...really? At home, this is a phrase that unconsciously floats through my mind on those days when I am watching my picky toddlers and need to make them something for lunch. What else is going through my mind in such a moment? Well, Ezra will eat, or at least try, almost anything. But, he loves cheese in nearly any form. Joey, well, will eat hot dogs, fries, mac and cheese, and ocassionally chicken nuggets. Not much else passes his discerning gaze, let alone his lips. But, he at least also loves cheese. So, I reason that if I add cheese, perhaps I can make it look good enough to eat or perhaps cover up that little pea so he does not see it as he tries the food.

What do I know for sure though? They both like cheese. They are both more or less picky. But, is my mental statement above really a theory based upon the evidence that I have? Absolutely not. It is closer to a hypothesis, if anything. Really though, it is not even that. But, let us assume that it is at least a hypothesis. Why is it not a theory? Well, according to Steven Hawking (who just might know something about this), it does not satisfy either of the conditions laid out above. First, I am only applying cheese to this unique meal, one meal in the span of time. While I have applied cheese to other meals in the past hoping for a similar result, there were definitely other variables that were not adequately controlled for me to isolate cheese as the reason that the food was or was not eaten. So, even if my toddlers eat this meal, I cannot add this to my other positive cheese supplementing experiences in order to form a model for toddler meal cheese application. After all, I can only make a deductive argument about this one particular meal. My goal in producing a theory would be to attempt to satisfy an inductive argument that cheese application to a particular meal or possibly any meal at any time or place, would make it possible for my toddler to consider savoring their parent's culinary delights.

The fact is, not only can I not produce a model for cheese application based upon my limited observations, I certainly do not have enough basis to be able to predict that, in perpetuity, should I apply cheese to my toddler's meals, they will always joyously consume them in blissful indifference to any other ingredients, no matter how putrid those ingredients have seemed to my toddlers in the past (Joey's list is long here -- starting with anything containing chlorophyll).

To summarize my mental prognostications:

1) I can only make a single deductive argument in terms of this one meal as I did not adequately control other variables in previous meals where cheese application was used;

Therefore, I cannot produce a model that predicts an answer to an inductive argument for cheese application in all cases.

2) Since I cannot produce an adequate model for cheese application, I cannot therefore use this meal or any other experience to make an adequate prediction of what they will eat, should I apply cheese.

Therefore, I cannot call this a theory.

So, perhaps if all of us attempted to use the word "theory" correctly, there would be less confusion amongst the American populace when it comes to what scientists mean when they use the word.

Here is a suggestion. In my classroom used to hang a poster that outlined alternative words to use instead of insulting someone or complaining about something using expletives commonly used by teenagers (who tend to be much less picky with their food, by the way). Let's consider some substitutions for our situation:

Words to use to clear up confusion over the word "theory"

hypothesis (use this one sparingly though...we don't need MORE confusion :))

I would speculate that...

I assume that...

I suppose that...

My guess would be...

I have a premise that...

I would postulate that...(use this one sparingly also, lest my math teacher friends become angered)

I have an idea, ...

I propose that...

A quick look in that oh so forgotten reference book, the thesaurus, provides a plethora of preferable meritorious substitutions for "theory". Let's explore using them :)! Perhaps once we solve this dilemma, some of the conflict between religion and science will cease also.

My wife tells me that she is making rice balls with some vegetable purees hidden within them, at this very moment, for our picky toddlers (peas are banned from our house now, Ezra has shoved too many up his nose). And, yes, they contain cheese! Yum! Best of luck to her!

Joey, when he sees the carrot through the cheese...

Wednesday, January 4, 2012

The Star of Bethlehem

The Star of Bethlehem has been an enigma for 2000 years. What was it exactly? As we near the end of Christmastide, it is worth an exploration. Is there a fascinating confluence of faith and good science here? Or, is it simply a mythological plot device meant to bolster a story that some felt needed a bit of divine gravitas?

Few people would argue the latter. Most take the star quite seriously. And why not? There is nothing in the Gospel accounts of Matthew and Luke to suggest that the story was embellished with any intent to mislead. It seems to be a genuine event which led three very learned men from somewhere in the east, perhaps modern Iraq or Iran to Bethlehem. Perhaps, given their knowledge of Jewish scripture and prophecy, they were a remnant of the Jews who were exiled to Persia or Babylon but never returned to Israel. It is difficult to say for sure. In the U.S., we like to celebrate the star, the arrival of these men, the shepherds, etc. all at once in our nativity scenes. In reality, it is certainly very likely that they did not arrive to celebrate Christ's birth until some time afterward. In the Orthodox traditions, they celebrate this event on the Epiphany, January 6th, rather than at Christmas. Whenever it really happened, it is a truly fascinating story with potentially awesome astronomical story behind it.

So, what was this star that heralded such a momentous event in human history? This has been the subject of a great deal of debate over the centuries. One great place to start our modern exploration is the website bethlehemstar.net. There, you can read the list of qualifications they have compiled that any candidate star must fulfill. It's long, based upon scripture, prophecy, and its purported behavior. Here is the list:

1) It signified birth

2) It signified kingship

3) It had a connection with the Jewish nation

4) It rose in the east, like other stars

5) Herod didn't know when it appeared

6) It endured over time

7) It was ahead of the Magi as they went south from Jerusalem to Bethlehem

8) It stopped over Bethlehem

What a tall order! Personally, I see nothing wrong with this list. In thinking about the last 5, however, it is easy to rule out some of the explanations that have been proposed over the years:

1) A meteor -- Dramatic, but is fails on #'s 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and possibly others as well.

2) A comet -- In those days, comets were regarded as bad things. A bigger problem, however, is that there do not appear to have been any comets to see in either 2 or 3 B.C., the likely candidates for Christ's birth year. Also, Herod would have likely seen it. So, they aren't good candidates.

3) A Nova or Supernova -- Here is a neat professional article arguing for just that! They argue that it either occurred in a globular cluster in our galactic halo or in the nearby Andromeda galaxy. It is a great read...the author has really done a great job reasoning it out. So, this is actually a good candidate, even if this event was not necessarily recorded by ancient astronomers, as they often were.

4) A triple conjunction of Jupiter around the star Regulus in the constellation Leo. This is the Bethlehemstar.net argument, and it is also quite compelling. Check out the website for a more in-depth read.

I do not have a definitive answer on the question of the star. But, this seems to me to be an excellent example of a positive confluence of faith and science. The Bible, actually, is quite full of astronomical observations, so it is worth a read of some of those for anyone interested. One can spend a serious chunk of time marveling at how ancient people so deeply appreciated the heavens that most of us, with our GPS units and so forth, take for granted. So, I love these kinds of explorations! They lead me to wonder at the grandeur of the whole thing that we call the universe. This is a case where, as a scientist, I find my faith bolstered by a significant account of logical evidence -- a case where science and faith find some common ground.

Merry Christmas! Happy Epiphany!

Few people would argue the latter. Most take the star quite seriously. And why not? There is nothing in the Gospel accounts of Matthew and Luke to suggest that the story was embellished with any intent to mislead. It seems to be a genuine event which led three very learned men from somewhere in the east, perhaps modern Iraq or Iran to Bethlehem. Perhaps, given their knowledge of Jewish scripture and prophecy, they were a remnant of the Jews who were exiled to Persia or Babylon but never returned to Israel. It is difficult to say for sure. In the U.S., we like to celebrate the star, the arrival of these men, the shepherds, etc. all at once in our nativity scenes. In reality, it is certainly very likely that they did not arrive to celebrate Christ's birth until some time afterward. In the Orthodox traditions, they celebrate this event on the Epiphany, January 6th, rather than at Christmas. Whenever it really happened, it is a truly fascinating story with potentially awesome astronomical story behind it.

So, what was this star that heralded such a momentous event in human history? This has been the subject of a great deal of debate over the centuries. One great place to start our modern exploration is the website bethlehemstar.net. There, you can read the list of qualifications they have compiled that any candidate star must fulfill. It's long, based upon scripture, prophecy, and its purported behavior. Here is the list:

1) It signified birth

2) It signified kingship

3) It had a connection with the Jewish nation

4) It rose in the east, like other stars

5) Herod didn't know when it appeared

6) It endured over time

7) It was ahead of the Magi as they went south from Jerusalem to Bethlehem

8) It stopped over Bethlehem

What a tall order! Personally, I see nothing wrong with this list. In thinking about the last 5, however, it is easy to rule out some of the explanations that have been proposed over the years:

1) A meteor -- Dramatic, but is fails on #'s 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and possibly others as well.

2) A comet -- In those days, comets were regarded as bad things. A bigger problem, however, is that there do not appear to have been any comets to see in either 2 or 3 B.C., the likely candidates for Christ's birth year. Also, Herod would have likely seen it. So, they aren't good candidates.

3) A Nova or Supernova -- Here is a neat professional article arguing for just that! They argue that it either occurred in a globular cluster in our galactic halo or in the nearby Andromeda galaxy. It is a great read...the author has really done a great job reasoning it out. So, this is actually a good candidate, even if this event was not necessarily recorded by ancient astronomers, as they often were.

4) A triple conjunction of Jupiter around the star Regulus in the constellation Leo. This is the Bethlehemstar.net argument, and it is also quite compelling. Check out the website for a more in-depth read.

I do not have a definitive answer on the question of the star. But, this seems to me to be an excellent example of a positive confluence of faith and science. The Bible, actually, is quite full of astronomical observations, so it is worth a read of some of those for anyone interested. One can spend a serious chunk of time marveling at how ancient people so deeply appreciated the heavens that most of us, with our GPS units and so forth, take for granted. So, I love these kinds of explorations! They lead me to wonder at the grandeur of the whole thing that we call the universe. This is a case where, as a scientist, I find my faith bolstered by a significant account of logical evidence -- a case where science and faith find some common ground.

Merry Christmas! Happy Epiphany!

Friday, December 16, 2011

The First "Earth-like" Planet Discovered!

Image: Caltech/NASA -- Artist's Impression of new

planet Kepler 22b

I have often wondered what the reaction would be in the religious community if life were ever discovered outside of earth. Throughout all of human history, most major faiths, Christianity included, have seen the earth and its inhabitants as being quite special and unique. Up until the last 500 years, earth was still considered to be the center of the universe, surrounded by planets, the moon, and the sun in orbit around it and the stars making up some distant firmament likened to pin holes in a black sheet draped over all of the above. What a picture! It makes sense though, when you think about it. Explanations provided by religion aside, this pretty well described the observable universe based upon the tools and knowledge that were available to our ancestors.

Changing these ideas took what was, at the time, a great deal of indirect international collaboration. The Polish astronomer Copernicus helped us correct Ptolemy's crazy geocentric system of epicycles and deferents by placing the sun at the center of it all instead. Unfortunately, his still very Aristotelian views kept the orbits too circular for that model to be widely accepted or, more importantly, useful for prediction. Not long after this, the German mathematician Johannes Kepler gave us three laws that govern how planetary orbits work. These laws made the Copernican heliocentric theory not only more palatable but much superior to the Ptolmaic model. Galileo, an Italian, popularized the idea further, which brought a great deal of attention to it...and also to him. He is thought to have been a very vain man, but the experience that he had as a result of his 1633 inquisition trial certainly forced a fair amount of humility out of him. He was a religious man and though not the most faithful Catholic in some ways, he was certainly deferential to the opinion and orders given to him by the inquisition. Explanations about why he was summoned before the inquisition are often simplistically reduced to his belief and acceptance of the heliocentric hypothesis, even though he was really summoned for disobeying an order not to teach the idea. Regardless, this is one of the noteworthy events that eventually led us into the modern scientific revolution and officially began the separation of science and faith.

I recount this story because it illustrates a major event in the confluence of science and faith. Galileo et al., challenged the deeply held convictions and beliefs of the church. This was not the first time this ever happened and it will not be the last...which brings me back to my original pondering...

As Christians, what beliefs about the uniqueness of earth will we strive to cling to should NASA or some other researcher finally discover the existence of life outside of earth? The probabilities, however lacking in empirical evidence for support, are against earth's uniqueness. The discovery of Kepler 22b recently, even with no evidence of life at the moment, has shattered any notion that earth could be the only place where life as we know it is possible. If life is found, would we make a distinction between microbial life and intelligent life? How does the story of the garden of eden figure into the theology of those who take that story to be literally historically correct? Will some christians refuse to even believe the plain evidence of life when presented?

I would like to think that we are past the age of witch hunts and inquisitions, at least here in the west. Galileo was finally pardoned in 1992, removing an unspoken barrier between science and faith that had existed since his conviction in 1633. While this branch of the church had already long since made its own strides in coming to an understanding with science, many (certainly not all) protestant christians still cling to a version of science that does not fit the same philosophical model as that claimed by mainstream scientists (that of the skeptical research interested in falsifiability, reproducibility, and testability). Their view starts with a model provided by their interpretation of a literal english translation of scripture, and attempts to fit evidence to that model, thereby creating a completely different interpretation of the same evidence. In traditional science, evidence leads to a model/theory which is used for prediction and explanation (Theory is a loaded word in these discussions...and might merit a forthcoming post by itself). Consequently, it is very likely that large swaths of christians would simply ignore or re-interpret the evidence in order to fit it to their preferred model, no matter how incontrovertible the mainstream explanation of that same evidence might be.

I hope that this will not be the case. An avid fan of Star Trek, I have also hoped that one day we could meet other intelligent species from beyond our solar system. I have never seen a conflict between what the Bible tells us -- as it talks entirely about us here on earth -- and the possibility of life outside of earth's creation. It never alludes to, nor disavows, the presence of life beyond this planet. I do not think it was much on the minds of the early Jewish writers, though I could be wrong on that one!

planet Kepler 22b

I have often wondered what the reaction would be in the religious community if life were ever discovered outside of earth. Throughout all of human history, most major faiths, Christianity included, have seen the earth and its inhabitants as being quite special and unique. Up until the last 500 years, earth was still considered to be the center of the universe, surrounded by planets, the moon, and the sun in orbit around it and the stars making up some distant firmament likened to pin holes in a black sheet draped over all of the above. What a picture! It makes sense though, when you think about it. Explanations provided by religion aside, this pretty well described the observable universe based upon the tools and knowledge that were available to our ancestors.

Changing these ideas took what was, at the time, a great deal of indirect international collaboration. The Polish astronomer Copernicus helped us correct Ptolemy's crazy geocentric system of epicycles and deferents by placing the sun at the center of it all instead. Unfortunately, his still very Aristotelian views kept the orbits too circular for that model to be widely accepted or, more importantly, useful for prediction. Not long after this, the German mathematician Johannes Kepler gave us three laws that govern how planetary orbits work. These laws made the Copernican heliocentric theory not only more palatable but much superior to the Ptolmaic model. Galileo, an Italian, popularized the idea further, which brought a great deal of attention to it...and also to him. He is thought to have been a very vain man, but the experience that he had as a result of his 1633 inquisition trial certainly forced a fair amount of humility out of him. He was a religious man and though not the most faithful Catholic in some ways, he was certainly deferential to the opinion and orders given to him by the inquisition. Explanations about why he was summoned before the inquisition are often simplistically reduced to his belief and acceptance of the heliocentric hypothesis, even though he was really summoned for disobeying an order not to teach the idea. Regardless, this is one of the noteworthy events that eventually led us into the modern scientific revolution and officially began the separation of science and faith.

I recount this story because it illustrates a major event in the confluence of science and faith. Galileo et al., challenged the deeply held convictions and beliefs of the church. This was not the first time this ever happened and it will not be the last...which brings me back to my original pondering...

As Christians, what beliefs about the uniqueness of earth will we strive to cling to should NASA or some other researcher finally discover the existence of life outside of earth? The probabilities, however lacking in empirical evidence for support, are against earth's uniqueness. The discovery of Kepler 22b recently, even with no evidence of life at the moment, has shattered any notion that earth could be the only place where life as we know it is possible. If life is found, would we make a distinction between microbial life and intelligent life? How does the story of the garden of eden figure into the theology of those who take that story to be literally historically correct? Will some christians refuse to even believe the plain evidence of life when presented?

I would like to think that we are past the age of witch hunts and inquisitions, at least here in the west. Galileo was finally pardoned in 1992, removing an unspoken barrier between science and faith that had existed since his conviction in 1633. While this branch of the church had already long since made its own strides in coming to an understanding with science, many (certainly not all) protestant christians still cling to a version of science that does not fit the same philosophical model as that claimed by mainstream scientists (that of the skeptical research interested in falsifiability, reproducibility, and testability). Their view starts with a model provided by their interpretation of a literal english translation of scripture, and attempts to fit evidence to that model, thereby creating a completely different interpretation of the same evidence. In traditional science, evidence leads to a model/theory which is used for prediction and explanation (Theory is a loaded word in these discussions...and might merit a forthcoming post by itself). Consequently, it is very likely that large swaths of christians would simply ignore or re-interpret the evidence in order to fit it to their preferred model, no matter how incontrovertible the mainstream explanation of that same evidence might be.

I hope that this will not be the case. An avid fan of Star Trek, I have also hoped that one day we could meet other intelligent species from beyond our solar system. I have never seen a conflict between what the Bible tells us -- as it talks entirely about us here on earth -- and the possibility of life outside of earth's creation. It never alludes to, nor disavows, the presence of life beyond this planet. I do not think it was much on the minds of the early Jewish writers, though I could be wrong on that one!

Wednesday, December 14, 2011

A Grand Unification?

Recently I had the pleasure of reviewing some video clips for potential inclusion in my astronomy lesson plans. I knew that I wanted something short but exciting to catch their interest. We had been discussing black holes, which are interesting to high school students anyway, but are also not easy to understand. My own understanding of the math behind them is severely lacking and my ability to answer some of the really good but unexpected questions that I invariably get from students is limited. However, we have fun with it. They enjoy the thought experiments that easily emanate from such subject matter. Such as,

"Katie and Zach are going to be the first scientists to study a black hole. Zach has volunteered to potentially trade his life for the eternal fame that will come with being the first human to enter a black hole. What would Katie see as Zach approaches the event horizon and what would Zach experience?"

This leads to discussions on time dilation, the speed of light, the ability for the two explorers to communicate (or not!), tidal forces, and -- the favorite -- "spaghettification". It's always a good discussion and one that I look forward to every year.

The problem is, when discussing black holes and the physics involved, like those theoretical physicists who are actually on the cutting edge of studying them, I run out of explanations when it comes to what happens when one reaches the center of the black hole, a point of zero volume but infinite mass and density. All known laws break down in there and we really have no good explanation for it!

This isn't the only subject with which I struggle in this manner. Later in the year, we will talk about string theory. The goal for string theorists is to prove that string theory can be used as a "Grand Unified Theory" that will unite our understanding of the forces that govern how large and fast things work, such as gravity (General Relativity), and the forces that govern how tiny particles work, such as the strong and weak nuclear forces and electromagnetism (Quantum Mechanics).

While science does not yet have such a theory, and even if it did, it will likely not provide an answer to everything for which we have questions, it does an excellent job of providing a way for us to explore the empirical world in order to figure out how it works and to better our lives here on earth. Science has proven itself time and again as the most powerful tool humanity has in unlocking the secrets of the known physical universe. However, it does have its limitations...

Enter faith/religion/theology. There are some questions that science cannot adequately answer. Psychologists and those who study the human mind have their ideas about how we form our understanding of morality and also why we have a need to seek out spiritual things. But, these explanations always fall short. What is clear is that there is a continuous absolute moral thread that binds all of humanity. It could be called a foundational morality, perhaps, but it is there and some of that can be seen in all of the world's religions. Even atheists adhere to it. Other spiritual convictions, such as a belief in an afterlife, our unique and pervasive self-awareness, our need to live outside of ourselves, our desire to overcome our faults -- these are things that can, perhaps, be supported with phsychological research, but not explained.

Unfortunately, there are many scientists who do not fully understand religion and we have many Christians who do not really understand science. Organizations like Answers in Genesis are a prime example of the latter. Their understanding of the nature of scientific investigation, reporting, peer review, reproducibility, etc. is vastly lacking, while they claim to be the real scientists in the room. In fact, their conduct and writings are so antagonistic to science and scientists alike that there work only serves to further alienate a public from science which also tends to be relatively scientific illiterate. This is not to insult the public, but only to point out that science is not an easy area to understand and it is something, like theology, that takes years of study to fully grasp.

Likewise, people like Richard Dawkins and organizations like American Atheists are just as bad. Though, I sometimes think that if Christians in the U.S. were more Christian, these individuals and groups would not be so prominent! Regardless, they do not work to elevate the conversation, but only serve to continue to cause it to sink into the abyss.

None of these folks, as vocal as they are, work to make any progress in our understanding of the world around us or our need for God.

There are others out here who do. Biologos is one such organization. The Roman Catholic Church, ironically, is another. While I am not Catholic myself, I have always admired the attempts, and strides, that this church (Catholics would say THE church) has made to find some common ground between faith and science. Their record on this historically, to be sure, is not a pristine one -- poor Galileo -- but their work since has been more than redemptive on this front.

In my own life, and my search for a church home these last few years, this issue has followed me around. Being a geology and astronomy teacher who has no problem with an old earth and evolutionary ideas, I have not been able to stay in churches, however life-giving they are, who are antagonistic to science. I am surely not the only person who has desired to attend in these places, but found that they cannot because sometimes Christians who are more "fundamentalist" in their thinking tend to elevate issues of origins and creation to the level of dogma rather than allowing for doctrinal freedom. This conflict has made my search, and my family's search, for a church home more problematic than necessary.

I contend that this conflict should not exist. I intend to contribute to a positive discussion of the boundaries, and commonalities, between science and faith in this space in the hopes that I can find some personal peace on the issue. In the process, I hope that these posts on this blog will help others who feel similarly also. Perhaps, in the future, we will yet see hope for a grand unification of science and faith!

I call this blog "General Revelations" because its goal is to explore what theologians call general revelation, which is in part defined by the beauty that we see around us in the natural world. Perhaps this "General Revelation" is the perfect place to start looking for the common ground that we seek.

"Katie and Zach are going to be the first scientists to study a black hole. Zach has volunteered to potentially trade his life for the eternal fame that will come with being the first human to enter a black hole. What would Katie see as Zach approaches the event horizon and what would Zach experience?"

This leads to discussions on time dilation, the speed of light, the ability for the two explorers to communicate (or not!), tidal forces, and -- the favorite -- "spaghettification". It's always a good discussion and one that I look forward to every year.

The problem is, when discussing black holes and the physics involved, like those theoretical physicists who are actually on the cutting edge of studying them, I run out of explanations when it comes to what happens when one reaches the center of the black hole, a point of zero volume but infinite mass and density. All known laws break down in there and we really have no good explanation for it!

This isn't the only subject with which I struggle in this manner. Later in the year, we will talk about string theory. The goal for string theorists is to prove that string theory can be used as a "Grand Unified Theory" that will unite our understanding of the forces that govern how large and fast things work, such as gravity (General Relativity), and the forces that govern how tiny particles work, such as the strong and weak nuclear forces and electromagnetism (Quantum Mechanics).

While science does not yet have such a theory, and even if it did, it will likely not provide an answer to everything for which we have questions, it does an excellent job of providing a way for us to explore the empirical world in order to figure out how it works and to better our lives here on earth. Science has proven itself time and again as the most powerful tool humanity has in unlocking the secrets of the known physical universe. However, it does have its limitations...

Enter faith/religion/theology. There are some questions that science cannot adequately answer. Psychologists and those who study the human mind have their ideas about how we form our understanding of morality and also why we have a need to seek out spiritual things. But, these explanations always fall short. What is clear is that there is a continuous absolute moral thread that binds all of humanity. It could be called a foundational morality, perhaps, but it is there and some of that can be seen in all of the world's religions. Even atheists adhere to it. Other spiritual convictions, such as a belief in an afterlife, our unique and pervasive self-awareness, our need to live outside of ourselves, our desire to overcome our faults -- these are things that can, perhaps, be supported with phsychological research, but not explained.

Unfortunately, there are many scientists who do not fully understand religion and we have many Christians who do not really understand science. Organizations like Answers in Genesis are a prime example of the latter. Their understanding of the nature of scientific investigation, reporting, peer review, reproducibility, etc. is vastly lacking, while they claim to be the real scientists in the room. In fact, their conduct and writings are so antagonistic to science and scientists alike that there work only serves to further alienate a public from science which also tends to be relatively scientific illiterate. This is not to insult the public, but only to point out that science is not an easy area to understand and it is something, like theology, that takes years of study to fully grasp.

Likewise, people like Richard Dawkins and organizations like American Atheists are just as bad. Though, I sometimes think that if Christians in the U.S. were more Christian, these individuals and groups would not be so prominent! Regardless, they do not work to elevate the conversation, but only serve to continue to cause it to sink into the abyss.

None of these folks, as vocal as they are, work to make any progress in our understanding of the world around us or our need for God.

There are others out here who do. Biologos is one such organization. The Roman Catholic Church, ironically, is another. While I am not Catholic myself, I have always admired the attempts, and strides, that this church (Catholics would say THE church) has made to find some common ground between faith and science. Their record on this historically, to be sure, is not a pristine one -- poor Galileo -- but their work since has been more than redemptive on this front.

In my own life, and my search for a church home these last few years, this issue has followed me around. Being a geology and astronomy teacher who has no problem with an old earth and evolutionary ideas, I have not been able to stay in churches, however life-giving they are, who are antagonistic to science. I am surely not the only person who has desired to attend in these places, but found that they cannot because sometimes Christians who are more "fundamentalist" in their thinking tend to elevate issues of origins and creation to the level of dogma rather than allowing for doctrinal freedom. This conflict has made my search, and my family's search, for a church home more problematic than necessary.

I contend that this conflict should not exist. I intend to contribute to a positive discussion of the boundaries, and commonalities, between science and faith in this space in the hopes that I can find some personal peace on the issue. In the process, I hope that these posts on this blog will help others who feel similarly also. Perhaps, in the future, we will yet see hope for a grand unification of science and faith!

I call this blog "General Revelations" because its goal is to explore what theologians call general revelation, which is in part defined by the beauty that we see around us in the natural world. Perhaps this "General Revelation" is the perfect place to start looking for the common ground that we seek.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)